The Sought After USVI Ingot Company Silver Bars & Rounds

- silverbarstacker

- Sep 6, 2024

- 13 min read

Silver collectors and investors are always on the lookout for new and exciting varieties of silver bars and rounds. Here at Silver Bar Stacker, we specialize in some of the more common vintage private refiners from the turn of the century such as Engelhard, Johnson Matthey, USVI Ingot Company, Sunshine Mining, Bunker Hill, and more.

In this blog post, we re-share a series of blog posts by a former USVI Ingot Company employee to help fill in some of the gaps as it relates to the rich history of the small and short-lived operation. The original article with this information can be found here.

-------------------------------------------

Company Name: USVI Ingot Co.

Company Location: Anaheim, CA

Company Information: According to the California corporation search website, USVI was started in 1981 in Anaheim, California and last registered in 1985.

-------------------------------------------

Does anyone own any of these ingots?

-------------------------------------------

Hi. Those were the first type of ingots we made at USVI Ingot Co. We later turned to industrial techniques involving extrusion presses and punch presses with lots of subsequent tool and die expense. However, if someone wanted to go into small scale production using our first technique, the set up and production costs would be manageable. The product is a bit 'funky', but there must surely be a market out there for art pieces. These free-form edge ingots were stamped with dies originally created for making gold jewelry, and I always liked the artistic aspects about them. I don't remember if I mentioned the problems we had with dies cracking, but it was a chronic problem throughout our history. Most of the round dies pictured above eventually cracked under pressure. Instead of replacing them, Mr. Eichen opted to invest in a new method of ingot production, and that was the stacking one ounce art bars.

Our business was not the business of buying and selling silver. We offered our services for a fee to suppliers in the silver business. They sent the raw material and we made it into ingots for 50 cents each. We had partners who owned a gold refinery and a building, and it was they who helped us through a transition period where we rented a small corner and an office at a bronze art casting shop. We 'jobbed out' most of the work to other industrial businesses… a machine shop, a stamping house, a tumbling and burnishing shop, an extrusion manufacturer. I usually had to go and sit with the silver, or else we had to make elaborate check in and check out procedures. We kept moving from shop to shop until we found one place where three of the above services could be performed. The extrusion people came on as partners for awhile, and we moved there. Then they sold us the extrusion press and we moved to the gold refinery. Whew! I don't know how many people owned a piece of it along the way, but there were quite a few.

It's probably a lot more fun buying silver than it is making it. It was an interesting adventure while it lasted. It even might have been sustainable if we had kept things simple. A drop in silver prices is what ultimately ended the experiment, unfortunately.

-------------------------------------------

Yes, can you believe we worked so cheaply? That was the price for making 1 ounce stacking loaf bars. I think the faux Roman rounds cost a lot more to produce, mostly because of planchet production methods. For Mr. Eichen, it was all about getting to the point of nearly complete automation. It didn't turn out to be automated, far from it, but we tried. The production methods for the stacking bars were very interesting, and I will try to get the story written some day.

If you have photos of any USVI Ingot ingots that aren't in the original article, would you mind posting them or sending them to me? I could not afford to collect 10 oz. bars for myself, and I don't think I've found photos of all of them.

I think we offered a one ounce bar with a generic “1” on the obverse for clients who chose not to advertise their business name. Mostly we made stuff for A-Mark who shipped us many thousands of ounces. Anaheim Metal Co. were our partners. They owned the building where we eventually settled. They seem to be gone now, so I guess it's OK to talk about them. There was a precious metals trading company, a jewelry shop, a gold refinery, and a silver stamping business all under the same roof. Maybe some gemstone sales, too, but that was hush hush. Anyway, Anaheim Metal decided to leave their name off their products. Any 1 ounce ingots you find stamped Anaheim Metal were early, and few were produced.

I'm not recalling 10 oz. bars with the Anaheim Metal stamp, but that's not surprising… we had employees handling production when we made the larger bars. 10 oz. bars were simple and easy. Being larger, there was much less stress on extrusion dies. They were stamped in a small punch press and the finish dies were not over taxed. Burnishing was more problematic than usual, for they tended to scratch each other in the tumbler, so we had to burnish in small batches. Yes, good product. Easier than one ounce pieces. Highly desired on the market.

-------------------------------------------

As a young person, I never expected that I would become involved in the world of precious metals. I earned a degree in Anthropology, and spent a lot of time studying photography, which peripherally involves silver, but not in it's metallic form. I was a recent college graduate, and fell into the world of silver bullion collecting because of a chance meeting with an interesting neighbor. Two and a half years later, I had helped produce many thousands of one and ten ounce ingots. The silver market had peaked, and was losing steam when I ultimately left the company.

It has been many years since those days. I have a small collection of ingots that we produced at the USVI ingot Co. I tried to purchase one example of everything that was made, even some of the prototypes, and a Monex coin that I wasn't supposed to have because they had decided not to release them. I use these bits of silver now to reconstruct the story in my memory.

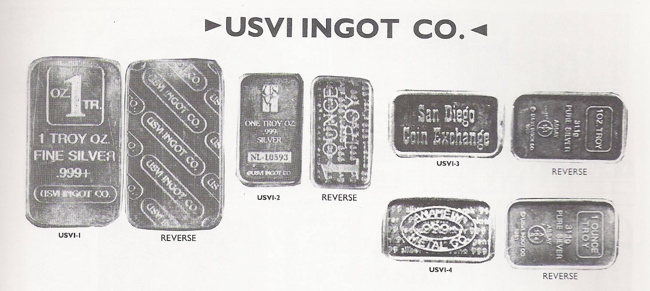

Recently acquiring a computer I decided to search for information about us. I learned our products are included in a publication called An Indexed Guide Book Of Silver Art Bars, 5th edition, published by J. Archie Kidd. I found some of our ingots for sale on eBay, and one vendor was kind enough to send me a scan of the Guide Book page. The printed list is incomplete. I also discovered Monex Trade Eagles had eventually been released and were for sale on ebay. I found our name on an online list of silver mints, but nothing else about us or the people and other companies involved.

Photos extracted from: An Indexed Guide book of Silver Art Bars, 5th ed., by J. Archie Kidd

I am here to tell the story of the USVI Ingot Co. since I am one of only a very few people who knows it. I don't know if it will be helpful to collectors, but I want to share this story in a place accessible to anyone who chances upon a silver, or even gold, ingot stamped with the name of the USVI Ingot Co., and to let the world know about the bullion stamped with our name, and a few designs without it.

It was a volatile time for the silver market. The highest prices had already peaked, but interest in acquiring bullion was still strong. Our company did not survive for long, but my understanding is that many other mints left the business later in the 1980s when silver prices bottomed out.

Our story is noteworthy for the techniques devised by Howard Eichen, our founder, to innovate some creative solutions to knotty production issues. His ultimate goal was to create a machine that would automate the fabrication of precious metal products, either ingots, medals, or jewelry findings. It was a noble enterprise, but a path filled with many obstacles. The tool steels and machinery available to us were prone to failure at high temperatures and pressures, and funding could not match the needs of the experiments. It was the fickleness of bullion collectors that caused our final demise as prices fell and interest waned.

Interest seems to be increasing again. It has been delightful to me to see our ingots being freely traded online. I will attempt to catalog every product we made, but my memory is a bit hazy on some details. For instance, I mention below that we had five dies for our original rounds, but there is a possibility of a sixth die. Some dies cracked early in the process, so if an early piece turns up that is not in this 'catalog' I'm creating, I would think it totally wonderful and would invite the finder to submit a photo. There were also a few gold pieces minted on a new, experimental hydraulic press with fully enclosed dies. I'm not sure if our name was stamped on them, or if they were the customer's dies. I was not privy to the gold minting project, the last new project before I left.

-------------------------------------------

The USVI Ingot Co. was the brainchild of Howard Eichen. He was a very inventive person whose mind was always busy thinking of new ways to make things, new designs for the world, another business to start up.

For me, the USVI Ingot Co. started in a tiny beachside cottage in Del Mar, CA, where I met Howard when I knocked on his door as part of my duties as a US Census Bureau enumerator. For him, the story began much further back, when he left his career in architecture, and began a new life as a jewelry designer.

He had moved to Antigua, Guatemala to remodel an historical hotel, but that project was canceled by a huge earthquake. Howard and his lady friend survived the tumbling adobe walls of their casa by crawling under the bed, but the hotel, the renovation just beginning, was completely destroyed. He then turned his creative talents to designing gold jewelry, with a special emphasis on inclusion of 24k gold elements into the designs. He loved the special gleam of soft pure gold, and used alloy gold only in areas that needed strength. He set up a workshop in Oaxaca, Mexico where he hired artisans to execute his designs. He often made trips to the US Virgin Islands, and planned to set up a business there one day. Our company's name came from that dream. He would have continued in the jewelry career indefinitely had it not been for the sudden, and disastrous, rise in gold prices in the late 1970s.

Feeling it time to start a new career, Howard returned to the US with ideas of using his knowledge of precious metals fabrication to create bullion pieces for collectors and investors. He had five cylindrical pieces of steel engraved with images, one of a bearded man with a wreath in his hair, as might be found on ancient coins, one of a sun with a face, a prancing bull, a ram's head, and two horses pulling a man in a chariot. These had originally been carved for stamping gold, but now his intention was to use these dies for prototype 999 silver ingots. His plan was to stay away from buying silver himself, and to find customers who wanted to convert their own bulk silver into coin and bar form for a fee.

My census duties were winding down, and Howard hired me to work with him on the silver project. The earliest ingots were produced in Howard's kitchen using techniques that were ancient, except for the modern tool we had for melting the metal. The molten silver was poured into a bucket of water to create 'shot'. The shot was thoroughly dried, then weighed into 1 oz. troy portions to be melted into blank coins. The rear die was a flat piece of engraved steel, and the top die was a cylinder. The planchet was set atop the flat die, the top die lined up, and the strike was made. The edges were uncontained in any way, so each piece bulged out around the edges in an unpredictable fashion. Each one of these original round ingots is unique in that respect.

We had an unusual device that looked like an electric coffee pot, but was actually a kiln, and we could put silver into it and heat it until it was molten. The molten metal was poured into graphite molds to create a planchet, a blank that is later stamped into a coin. The coffeepot kiln was problematic, since we could make only one pre-weighed planchet at a time, or multiple planchets with undetermined weight. Another problem was that the electric elements would often fail, and it was expensive to repair the temperamental appliance that was intended to melt gold. Silver melts at approx. 1800 degrees, much hotter than gold, and those temperatures are damaging to equipment.

There were a couple of ingots that were struck using a hand held die, and a guy with a sledgehammer… dangerous and inaccurate at the same time. Some other coins were squeezed between two dies with a hydraulic automobile jack imbedded in a steel frame. These methods were too slow and ineffective, so Howard found a shop with a stamping press where they were willing to help with our coining experiments.

I felt comfortable using ancient techniques and turning out ingots in small batches. I became involved in this enterprise because I thought I might learn something about jewelry making. But Howard had grander plans than just a small cottage industry. He had hired a sales representative, and we began receiving small orders for the crude round ingots. We needed to go into production in a serious way. The days of working in the beachfront kitchen were ending, and we began the search for partners, customers, and a place to do our manufacturing.

-------------------------------------------

These are three versions of the reverse die used on the original round ingots. The die at top was carved by Howard Eichen, and did not long survive the pressures of the stamping press. The two dies at the bottom were used for production. Bottom right die was used first, bottom left die came next.

The original round ingot packaging. I remember that some customers (stores) preferred to remove the packaging.

-------------------------------------------

Loaf Bars

A-Mark, second obverse design. 'loaf' bar ingot

Early loaf bar, reverse dies. The ingot on left shows the first style of reverse die. This might have been the only batch to bear the name of Anaheim Metal Co. The top most graphic changed to say 1 OZ. Troy with the next assay number. Both of these ingots say AMARK inside of an oval on the obverse. The ingot on the right shows some of the difficulty we sometimes had in obtaining a complete corner fill during the strike.

-------------------------------------------

Experimental ingots. Very few of these were produced, and they were not popular. The idea was to see what sort of edge formed using wide, shallowly engraved dies.

-------------------------------------------

Square Cornered Bars

-------------------------------------------

10 ounce ingots

-------------------------------------------

Monex Trade Eagle, obverse

Reverse

-------------------------------------------

This large flat bar was produced after my departure.

-------------------------------------------

Since writing those I have acquired photos of several more of our products. I am putting them here to make a complete (I hope) catalog of all silver bars and rounds made by the USVI Ingot Co. aka U.S.V.I. Ingot Co.

All the silver processed by the USVI Ingot Co. was originally large ingots (800oz through 1400oz) stamped Johnson Matthey or Engelhard or occasionally another well known refiner such as Northwest Territorial Mines. Silver was supplied by A-Mark, Monex, or Anaheim Metal Co. Two brothers had attempted to monopolize the silver market and control prices by buying up huge quantities of refined silver. They were successful enough that prices began to rise, almost to $50 per oz. Anti-trust courts ordered them to sell off assets, so many large precious metals firms stepped in to buy all that excess metal and control release onto the market. Our job was to convert the large silver pieces into smaller units.

The large bars were cut into chunks, melted in a floor furnace, and poured either into silver shot or molded billets. Shot was weighed, then kiln melted in small round graphite trays, creating melted planchets. Billets were extruded in a huge industrial machine to create ribbons of silver in various thicknesses and widths, then cut to length to make planchets. Weight was controlled by varying slightly the length of the cut using an electronic scale to monitor each piece as it was cut. All planchets were burnished with stainless steel shot in a tumbler. At this point the planchets were ready for stamping in a punch press or hydraulic press.

There are some paper ephemera items I remember which are not yet photographed, to my knowledge. It was promotional material several pages long. It was printed on white textured paper, was embossed with raised areas. There were silver foil decals (maybe stickers) that looked like our ingots, as well as several designs that were never stamped in silver metal. One of the ingots made in foil and featured in the brochure was the 1 oz. flat stacking bar which was produced.

Early rounds, 7 known styles

Quote from an email from Howard Eichen, designer of the early USVI Ingot Co. rounds and company founder: I'm thrilled that you have kept USVI alive. I have seven of the original intaglio sculptures that were reduced into coin size steel dies.

1. Roman Head 2. Chariot 3. Sun Symbol 4. Pisces 5. Rams Head 6. Bull 7. Mayan Head

4 reverse dies, early rounds

-------------------------------------------

Loaf bars stacked as they were designed to do. When I shipped ingots to a customer, they were first stacked and counted. Silver ten ingots high, ten wide, and ten deep were arranged on a table to make a group of 1000 pieces. It was a very impressive sight. They were counted by several people who all witnessed the packing of the shipping can and signed the paperwork. Regrettable I never photographed the display, so this small grouping I found online shall have to substitute.

5 loaf bar designs, designed to stack. Extruded, cut, burnished, stamped.

7 examples of loaf bar reverse dies, numbers continue past this point to..? I've seen as high as 189, but it might go higher.

Numbers 158 through 161 were the same outer die of the two piece die, only the numbered cylinder was changed.

150 early version, says Anaheim Metal 150-157 one piece, 158-161 two piece, shows double ring 158 protrudes 161 outer die is cracked, number tilted.

2 styles of bar ingots. flat stacking and loaf bar, extruded planchets

C. Rhyne flat stacking bar ingot

rear die example, flat stacking bar ingot. Rear dies were acid etched. This particular example has a cracked rear die.

-------------------------------------------

4 sizes of rounds. One is a prototype I believe, perhaps a very short run of ingots

The round in the center was made by USVI Ingot Co. The bar ingots are from Credit Suisse and Engelhard.

-------------------------------------------

10 oz. bars, stacking. Extruded, cut, burnished, stamped, hand numbered

-------------------------------------------

100 oz. bars. Extruded, cut, burnished, stamped. Very few made.

-------------------------------------------

1 oz. large flat bar. I have no memory of this item

-------------------------------------------

Monex products made by USVI Ingot Company, The Silver Eagle and the Trade Eagle. They were struck on a hydraulic press and have finished serrated edges. I believe the press and die sets became property of Monex and production moved to their facility. Planchets were punched from extruded ribbon, weight checked and adjusted, burnished, stamped. Cleanliness was essential, white glove clean, because any oil or grease created ghostly marks on the finished ingot.

-------------------------------------------

One more photo

Original packaging for the early rounds

If you want to view our USVI Ingot Company product offerings, you can do so here.

We have a large inventory of products that we source from reputable suppliers and that we verify the purity of using industry-standard Sigma Metalytics testing equipment: https://www.silverbarstacker.com

#Vintage #Silver #Engelhard #JohnsonMatthey #USVI #SunshineMining #SwissofAmerica #Gold #Bar #Round #Bullion #Rare #Shaq #Crypto #Bitcoin #Finance #Eagle #Prospector #Maple #Liberty #America #Canada #2ndAmendment #Food #Budget #Charity #Homeless #Music #Bass #Sigma #Metalytics #DraperMint #Chunky #Rolo #Ingot #SOA #Scotiabank #Bank #Howard #Eichen #Ingot

Kommentarer